On her way out of the classroom, Sara, a sophomore from Hong Kong majoring in journalism at Emerson College in Boston, was asked by one of her American classmates if she was from China.

"No!" Sara flatly refuted, "I'd be offended if people said I was from China."

Given the recent tension in Hong Kong, Sara did not want to disclose her full name.

Sara first became aware of her cultural identity as a Hongkonger when she was involved in the Umbrella Movement, a three-month occupation of a downtown area in Hong Kong back in 2014, to call for universal suffrage.

Describing herself as a Hongkonger would makes Sara proud. It gives her a sense of belonging to her home city.

On her Facebook page, most of her posts are about protests in Hong Kong.

"I'd say I'm from Hong Kong and they [her classmates] can ask me about what's going on [there]," Sara said.

She believes this is her way of contributing to her beloved city when she tells people on campus in Boston about what protesters in Hong Kong are facing. It’s her way of expressing her cultural identity.

Frances Hui Wing-ting, another student from Hong Kong at Emerson College, wrote an article "I am from Hong Kong, not China" for the university newspaper. It went viral.

"'I am from Hong Kong' has a special meaning. It means we value democracy and human rights," Frances explained.

In the article, Frances said it upset her to see the name of her home city listed as "Hong Kong, China" in the university's exchange programme document. She accused the university of not sufficiently "cognizant" and "knowledgeable" about Hong Kong.

"It's very offensive to ignore one's identity," Ms. Hui said.

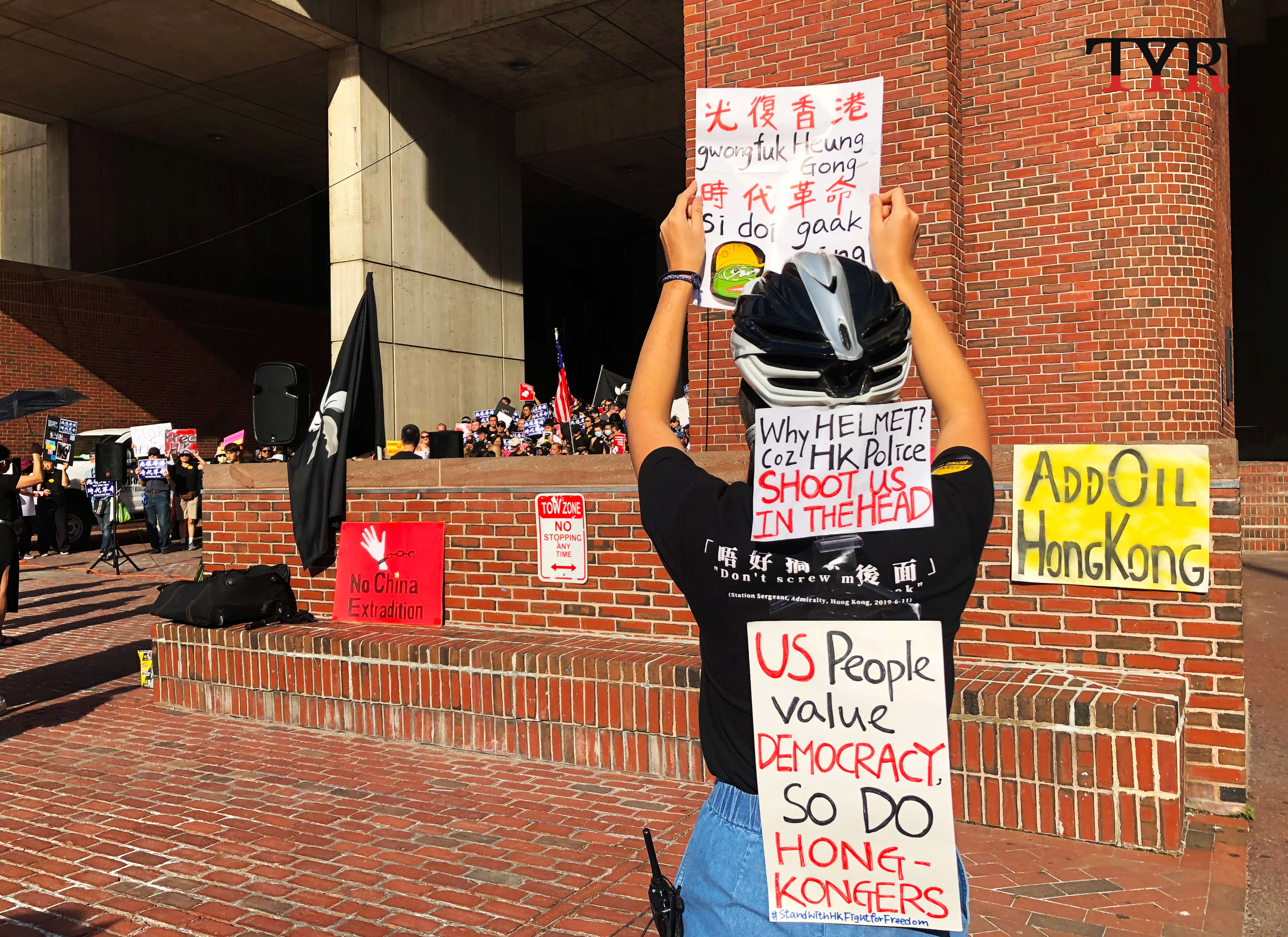

She has been organising marches and assemblies in support of the anti-extradition bill protests Hong Kong protests in Boston since June. On 22 September, around 400 protesters marched to Boston City Hall Plaza to call for the passing of the "Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019". The Act means the US will have to review Hong Kong’s state of autonomy every year in order to decide whether it should continue to be regarded as a separate economic entity from mainland China.

The question of a Hong Kong identity has become divisive between students from mainland China and those from Hong Kong at Emerson.

Raine Pan, a mainland Chinese student believes Hong Kong protesters' actions have gone too far and will destroy Hong Kong.

"I can understand that they [Hong Kong people] may find it unacceptable that a city [Hong Kong] governed under capitalism now belongs to a socialist country [China]," Ms. Pan said, "but they've gone far beyond freedom of speech and are provoking riots ."

She thought Frances' stories on Hong Kong did not reflect reality.

"She has made her cultural identity issue to a political-like statement with no reliable sources," Ms. Pan said, "it's [claiming oneself as a Hongkonger] okay in terms of cultural identity, but political identity is objective. They need to be separate."

According to a survey conducted by The University of Hong Kong in June, the number of residents in Hong Kong who identified themselves as "Hongkonger" has almost doubled since August 1997.

Only about 11 per cent of the respondents in the survey identified themselves as "Chinese".

Three days after Frances' article went online, the university newspaper published a letter.

In the letter, three Emerson students from mainland China Fu Xinyan, Liu Jiachen and Tu Xinyi, said they were worried that the article would lead to misunderstanding among ethnic groups on campus. They believed "Hong Kong, China" was the appropriate title for their university to use.

"By listing Hong Kong as a part of China, Emerson is following the region's [Hong Kong's] legal recognition," the letter read.

According to the Sino-British Joint Declaration, it was agreed between Britain and China that, Hong Kong would "be directly under the authority of the Central People's Government." As "Hong Kong, China", Hong Kong could develop its own economic and cultural relations with states, regions and relevant international organisations.

Tim Riley is a cultural studies academic at Emerson College.

"I would bet money the person who's referred to this person [Frances] as 'Hong Kong, China' did not intend to offend anybody, really just trying to be correct [for herself]," said Mr. Riley, "The intention was probably very innocent, but the effect could be very offensive [to other people]."

Mr. Riley said although the title "Hong Kong, China" is based on agreed terms in the Sino-British Joint Declaration of Hong Kong in 1997, it has overlooked Hongkongers who are now increasingly reluctant to be identified as Chinese. .

He believes the Hong Kong protesters are trying to press and clarify and seek transparency in the Hong Kong Government's relationship with China.

"Are we [talking on the side of Hong Kong people] going to be more defined ? Is Hong Kong going to fit under the definition that China imposes on Hong Kong? That to me seems to be the identity question that's at stake in the Hong Kong protests," said Mr. Riley.

《The Young Reporter》

The Young Reporter (TYR) started as a newspaper in 1969. Today, it is published across multiple media platforms and updated constantly to bring the latest news and analyses to its readers.

Policy Address 19/20: Carrie Lam rolls out economic measures for youth but misses the mark

Mass rally in London to call for second Brexit referendum

Comments