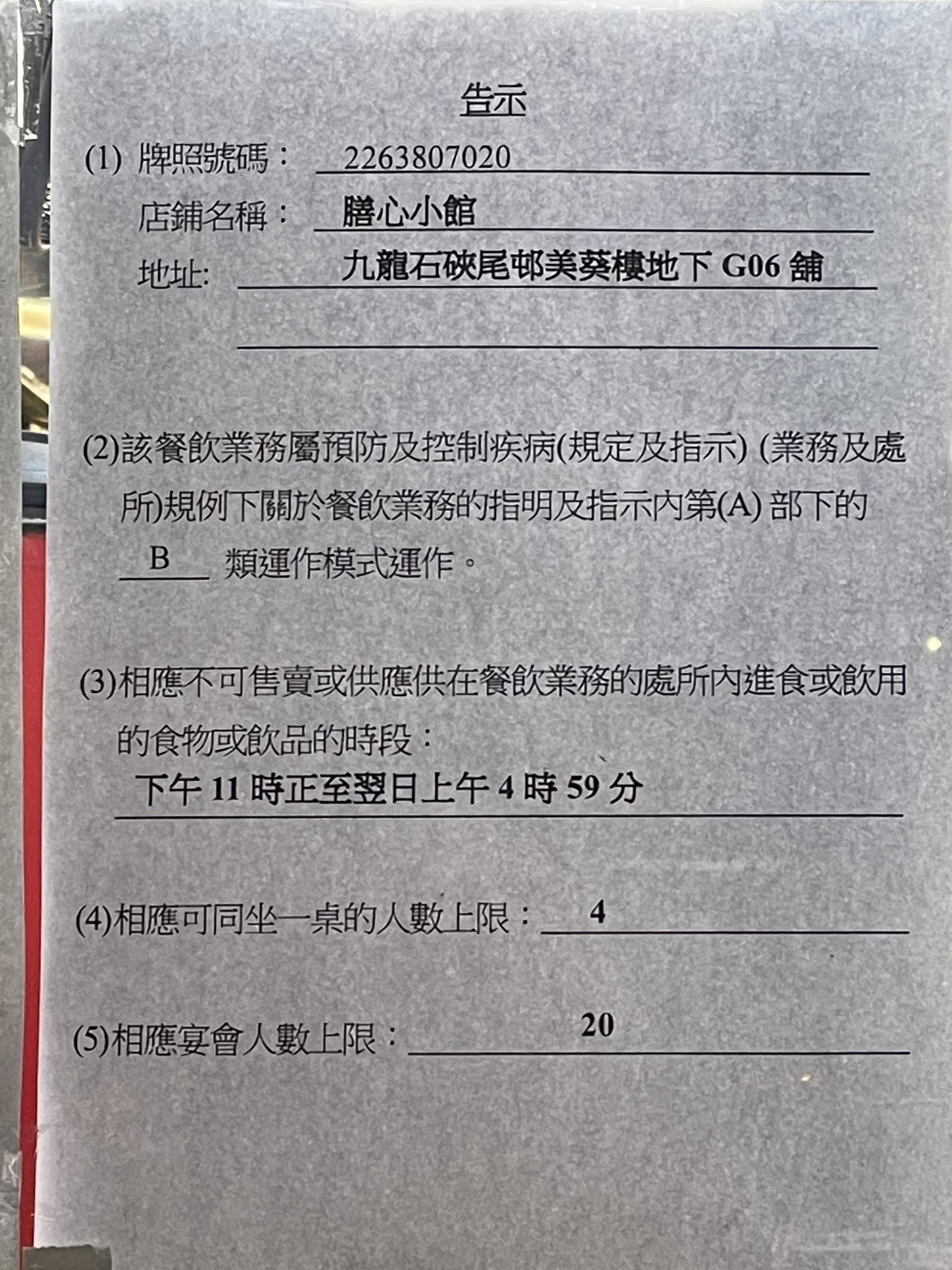

After the close of business on Dec. 8, Roy Lam took down the sign listing his restaurant as Type A and put up a Type B notice.

“There was no choice other than closing for good,” said Lam, the manager of Agape Garden, a small restaurant located in Sham Shui Po.

Starting tomorrow, type A modes of operation of restaurants would be cancelled, and diners who do not meet the exemption policy will be required to scan the QR code of the restaurant using the LeaveHomeSafe, a government contact tracing app during the pandemic.

“We made it to the last day,” Lam said.

The Agape Garden was not the only restaurant that was forced to use this mobile app from Dec. 9. With LeaveHomeSafe adding the function of connecting to the Hong Kong health code, the government asked customers to scan QR codes using the app before entering every type of restaurant.

This policy is set to meet Beijing’s standard on COVID-19 prevention and reopen the board with mainland China. However, about 500,000 Hong Kong residents still don’t have a smartphone in 2020, according to government statistics, and complaints also arose due to the deficiencies in arrangements for exempted people and private concerns.

Before the policy went into effect, there were four modes of operation of catering premises in Hong Kong. Type A restaurants had the loosest COVID prevention methods, they accepted customers not to leave their personal information, while the remaining types of restaurants were asked to collect the information by paper or the LeaveHomeSafe app.

The trade-off was that type A premises could not allow diners to eat in the restaurant after 6 p.m., and no more than two people were allowed at a table, compared with four in other types.

Though there were more restrictions on the operations of type A restaurants, Lam still adhered to it when he had choices.

Lam said he stuck to a type A restaurant because many people don’t have a smartphone in Sham Shui Po, a district with a high poverty rate, especially the elderly and children.

“They already have enough difficulties in their lives, and I don't want them to have any more troubles when it comes to eating,” said Lam. “I want to help them.”

After the implementation of the new policy, there are only three types of restaurants left, and the use of the LeaveHomeSafe app is mandatory, even for type B restaurants, which previously allowed diners to write their information on paper.

The Agape Garden was converted into a type B restaurant, which can provide in-house food in the evening. Yet Lam said more consumers ordered take-away and the whole revenue fell 40% in the week after the new policy.

“Our restaurant used to attract many elderly and children, with a lot of people don’t want to use the app,” Lam added. “Many of them left when they saw we needed them to record their visits.”

Some seats were put in the parking lot near Agape Garden, some middle school students were eating there because they were not allowed to bring a smartphone with them on school days.

“I really want to ask these children to eat in our restaurant, but the food department monitors us more strictly than big restaurants…” Lam said.

Only people younger than 15 or older than 65, the disabled, the homeless, and those unable to use a smartphone are exempted from using the app.

They still need to write their particulars on paper, including name, phone number, the date and time of arrival, if they want to eat in a restaurant. Children under 15 can avoid filling in the form when they have their parents accompanying them.

However, a visually impaired man, Henry Dang Bing-jip, chose to use the LeaveHomeSafe app because he was worried that his private information could be compromised by the staff of restaurants if he wrote on paper.

“It’s dangerous for me to give my ID card to staff in restaurants if I want to fill in a form, as I can’t see anything and don’t know what they will do to my information,” Dang said.

Although the government said visually impaired people could fill out basic information in advance either by themselves or through NGOs, and that the store staff only needed to help them record the date and time in the store, many blind people were refused to use pre-filled forms as the policy was just beginning to take effect.

“The government needs more publicity about the new policy on the exempted group,” Tony Sing Lei-lim, director of the Hong Kong Federation of the blind, said on social media because the public was still unfamiliar with the new arrangements.

Dang also met some trouble when using the app, many mobile apps he used can provide a voice guide but the LeaveHomeSafe app failed to support it, and he couldn’t find where the QR code is when scanning.

“The government is developing prominent QR codes and Braille for visually impaired people to help them find scanning positions,” Wong Shuk-han, Deputy Director of the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department, said in a press conference on Dec. 7.”

However, Dang hasn’t met such a design so far, and he thought this method was not very useful.

“With the prominent QR code I only know where it is, but the scales of QR codes are different, scanning them successfully is a different thing,” Dang said.

Whether the customers belong to the exempted group is claimed by the diners themselves, the staff has no right to check the authenticity of diners' information.

“Some girls in high school uniforms said they were under 15, and I couldn't check if that was true,” said Roy Lam.

Though the spokesman of the government said that staff only need to ensure the diners have used the LeaveHomeSafe app or have registered the needed information on paper, some cases of conflict over whether diners are in the exempted group occurred.

“The criteria for determining exempted persons were not clear enough, and we were afraid of being fined if we made a mistake in judgment,” said Lam.

The government has assured residents many times that data in the LeaveHomeSafe app is saved only on the user’s mobile device and in an encrypted format, but some still have privacy concerns. 47.9% of 712 respondents agreed or very much agreed that the government might use the personal data collected for purposes unrelated to the pandemic, according to the opinion polls made by the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies in April.

“Many of my customers and I don't trust the app's privacy policy and think it may be a tool for the government to track dissidents, so we tried to fill in papers instead of the app previously,” said Lam.

The Democratic Party called for the withdrawal of a blanket decision to use LeaveHomeSafe at restaurants a week before the new policy went into effect as they worried the growing scope of the use in the app could lead to personal data leaking at the programming level.

“The risk of privacy leakage is certainly higher in the form of filling in the paper, which leaves information on paper to some restaurants who will not always be dedicated to protecting diners' privacy,” Vincent Wong Wing, a radio presenter of Hong Kong Commercial Broadcasting said.

But Lam didn’t buy those words.

“You can’t change people’s minds by forcing us to use LeaveHomeSafe,” Lam said. “The resistance to using the app reflects many people's distrust of the government in a certain way.”

《The Young Reporter》

The Young Reporter (TYR) started as a newspaper in 1969. Today, it is published across multiple media platforms and updated constantly to bring the latest news and analyses to its readers.

Hydroponics: how an alternative farming method is paving the way for sustainable agriculture in Hong Kong

Lowest ever turnout under revamped LegCo Election system

Comments