Several foreign correspondents in Hong Kong have told TYR they feel a general sense of anxiety about their visa renewals after senior Financial Times editor Victor Mallet was denied permission to continue working in Hong Kong.

The president of the Foreign Correspondents' Club, Florence de Changy, told TYR that she could sense the anxiety among younger reporters and those who want to be posted in Beijing in the future.

"They will not show themselves too much on the stage and they will not host some speakers if the situation prevails," said Ms. de Changy, who works for Le Monde, a French newspaper, and Radio France International.

The Immigration Department rejected Mr. Mallet's work visa renewal months after he moderated a forum by Andy Chan Ho-tin, convenor of the banned pro-independence Hong Kong National Party, in August at the FCC.

Mr. Mallet was then offered a seven-day visitor permit to stay in Hong Kong when he arrived back from Bangkok on October 8. His attempted re-entry on November 8 was denied by the Immigration Department, with no reason given.

Ms. de Changy said Mr. Mallet had never been warned his visa would be at risk if he hosted that forum.

"Sometimes the [Hong Kong] government don't like what we do but they did not stop us from doing it," the FCC president added.

The FCC currently has 500 members who are journalists or correspondents.

Some 80 foreign media organisations have set up offices in the city, according to government statistics.

Several foreign correspondents pointed out the grey area the government left behind following Mr. Mallet's incident when they spoke to TYR, including those who have interviewed Andy Chan or covered stories about Hong Kong independence.

They declined to go into the specifics of their issues because their news organisations' codes of conduct prohibit them from giving opinions about stories they are covering.

"We don't know what is okay and what is not," said one of the correspondents, who has been based in the city for about four years.

"We are a bit like in Mao's era in my view," another senior correspondent commented. "When Xi Jinping spoke, suddenly there was a red line and [it] became a de facto rule."

Most non-permanent residents working in Hong Kong need to have their visas renewed every two years. By law, the granting of visas is at the discretion of the director of immigration.

The Immigration Department responded to email queries from TYR on Mr. Mallet's case, saying the Hong Kong government would not comment on individual cases.

Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor had criticised the FCC talk as "regrettable and inappropriate", but her government later toughened its language to "totally inappropriate and unacceptable" in a statement after the event.

In a letter Ms. de Changy addressed to the FCC members, seen by TYR, she also wrote that the central authorities had "explicitly asked" the FCC to cancel the talk.

"There were several direct conversations between Chinese representatives in Hong Kong and both Victor Mallet who, as First VP was the acting president during the whole episode, as well as myself," she wrote.

Rose Luqiu Luwei, a journalism professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, said the problem was that such a decision had harmed Hong Kong's reputation as China's most liberal city and the government paid "too high a price" in effect.

But she said she did not want to speculate on the government's motives.

"It wasn't necessary for the government to deny Mallet's visa," she said. "It was the FCC's collective decision [to hold the talk]."

Dr. Luqiu, who was a war correspondent during the Iraq War in 2003, deems the government's move to be "a signal to foreign journalists" and "an attempt to exert self-censorship."

She said she had been detained and deported by the Myanmar military junta in 2009, adding that visa revocation is common among authoritarian regimes.

Amnesty International researcher, Patrick Poon Kar-wai, believes the Hong Kong government "took advantage" of the FCC talk to muzzle the press freedom among foreign journalists and keep the press club in check.

"Victor Mallet has worked in Hong Kong for many years. Why did the situation (the visa rejection) happen so suddenly?" he asked. "The only reason is that he chaired Andy Chan's talk for the FCC."

The move was further viewed by Mr. Poon as a sign that pressure on press freedom has extended from local media to foreign journalists.

Mr. Mallet has been working for the Financial Times since 1986. He was based in Hong Kong as the Asia correspondent and editor from 2003 to 2008 and returned to Hong Kong from New Delhi to become the Asia news editor in 2016.

Since no official explanation for the rejection has been given so far, Ms. de Changy argues that the red line in deciding whether an applicant is to be granted a visa renewal is opaque and calls for clarity in the rules on visa renewal.

"It would be much better to have a clearer red line but we don't have it," she said.

She pointed out that Chinese President Xi Jinping warned in July last year that any attempt to endanger China's sovereignty and security was "an act that crosses the red line" and would be "absolutely impermissible."

She also joked that she should host an event called "What is the red line?" as she thinks it is a key question.

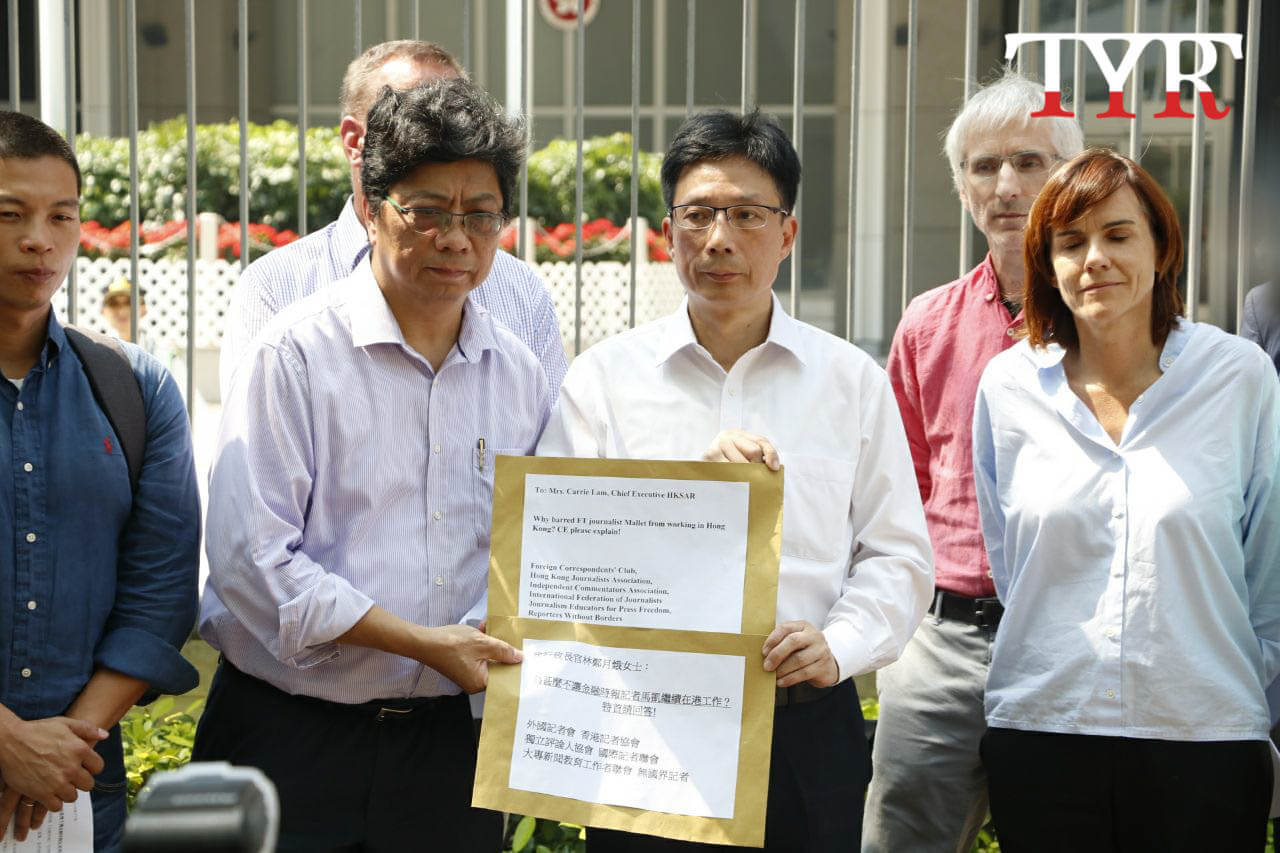

In early November, 19 former FCC presidents penned a joint statement urging the government to provide a full explanation of the rejection.

A number of high-profile incidents have affected the local media since the city was handed over to China in 1997, such as the sacking of veteran opinion journalist Li Wei-ling and the attacks on news commentator Albert Cheng Jing-han and former Ming Pao chief editor Kevin Lau Chun-to.

In a press conference Ms. Li held after being fired in February 2014, she argued that her abrupt dismissal was due to political reasons.

But Ms. de Changy, who has been working in the city for 11 years, said Mr. Mallet was the first case of a foreign journalist being denied a work visa.

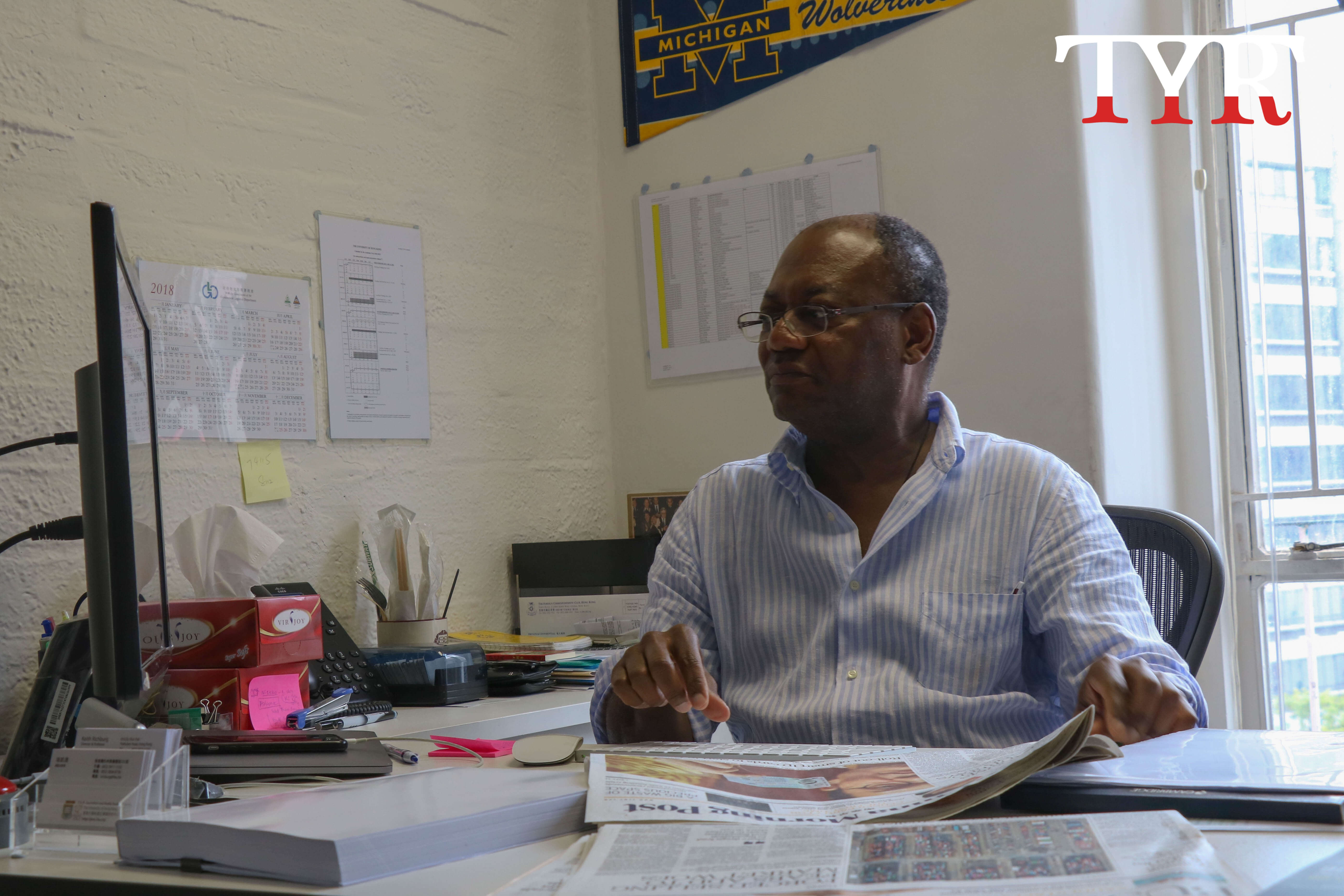

Keith Richburg, director of the University of Hong Kong's Journalism and Media Studies Centre, said the environment for journalists working in the city had become "much more strict" after the handover.

Mr. Richburg used to work in East Asia as a correspondent for The Washington Post from 1986 to 2013. He was also the president of the Hong Kong FCC in 1997.

The longtime journalist said people had never needed credentials to prove they were journalists when he first came to Hong Kong to help The Washington Post open a bureau in 1995.

"People just came in, worked, lived every few months and back," he said. "This was the easiest place in the world to come in for work, and can operate freely."

It was a common strategy for dictatorships to block certain correspondents from accessing the country by declining to renew their visas, he added.

In an article he wrote to Inkstone, a South China Morning Post digital news platform, in early October, he said he had been banned from Indonesia for two years since he wrote about how the president then had seized power in a coup.

Now the HKU journalism faculty director feels the government is telling the FCC what to do by "kicking foreign correspondents [out]."

Former Beijing bureau chief of Buzzfeed News, Megha Rajagopalan, wrote on Twitter that the foreign ministry in Beijing had refused to issue her a new visa in May this year after working there for six years.

"They say this is a process thing, we are not totally clear why," Ms. Rajagopalan's tweet reads.

In Hong Kong, the Bill of Rights Ordinance protects people's "right to freedom of expression" unless their speech causes harm to other people's rights or reputations or if their speech affects national security, public order, public health or morals.

In a United Nations Human Rights Council review meeting held in Geneva on November 6, Hong Kong chief secretary, Matthew Cheung Kin-chung, said concerns over the human rights situation in Hong Kong were "unwarranted, unfounded and unsubstantiated."

"We are firmly committed to protecting press freedom," he said in the meeting. "We do not exercise any censorship."

On November 18, Mr. Cheung reaffirmed that Mr. Mallet's incident had nothing to do with freedom of the press.

But according to the World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, the city's ranking has fallen from 18 in 2002 to 70 this year. The group has considered Hong Kong to have "noticeable problems" regarding press freedom since 2011.

RSF also set up its first Asia bureau in Taipei last year. In this year's index result, Taiwan was ranked the highest in Asia for press freedom for the sixth consecutive year.

In a film screening hosted by online news outlet Hong Kong Free Press on November 5, Asia bureau chief Cédric Alviani described Hong Kong as the "battlefront" resisting Beijing's suppression of free speech.

He said RSF would not open its office at the "battlefront" when asked why the group had chosen Taipei instead of Hong Kong.

Ms. de Changy also said some journalists expressed their preference to work in Taiwan rather than Hong Kong because they believed Taiwan was freer in terms of all kinds of liberties.

The Financial Times is still appealing the decision over Mr. Mallet's visa rejection.

Ms. de Changy thinks his case was a one-off.

But the relationship between the Hong Kong government and the FCC has deteriorated since then. Ms. de Changy confirmed that the chief executive had declined the club's invitation to its annual diplomatic cocktail reception although she was the guest of honour last year.

Enquiry emailed to the Chief Executive's Office about how the government can protect foreign journalists in the city from political pressures was forwarded to the Security Bureau and the Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau.

"The HKSAR Government is firmly committed to protecting the fundamental rights, including the freedom of expression, guaranteed by the Basic Law and the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance," the Security Bureau's statement reads.

The Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau replied that the Hong Kong government "maintains an environment conducive to the operation of a free and active press."

The CMAB added that both local and international media could "freely" and "rigorously" perform their role as a "watchdog over public affairs."

The New York Times digital editor, Jennifer Jett, succeeded Mr. Mallet as the FCC's first vice-president on November 17.

She replied to TYR's email enquiry, saying she did not have anything to add beyond the FCC statement which continues to call on the government to provide a reasonable explanation for its refusals to Mr. Mallet's re-entry and his visa renewal.

Ms. Jett has been living in the city since 2010. Both Ms. de Changy and she have already become permanent residents.

"I don't take my stay in Hong Kong for granted," Ms. de Changy said, however, despite her Hong Kong permanent residency.

"I sincerely believe that the Chinese authorities, as they are now, can do anything," she added. "You are not a citizen… As a foreigner, we must remember that we are all guests in this place."

《The Young Reporter》

The Young Reporter (TYR) started as a newspaper in 1969. Today, it is published across multiple media platforms and updated constantly to bring the latest news and analyses to its readers.

Hong Kong's news media faces practical challenges in face of global digitalisation

Legco By-election: pro-democracy camp's second defeat in Kowloon West

Comments