Buying train tickets, karaoke with friends, feeding ducks by a lake, or visiting art exhibitions. Those are some of the activities that “Siubak” and “Winter” enjoy with each other, not in reality, but in a virtual world. Both of them are young men in real life.

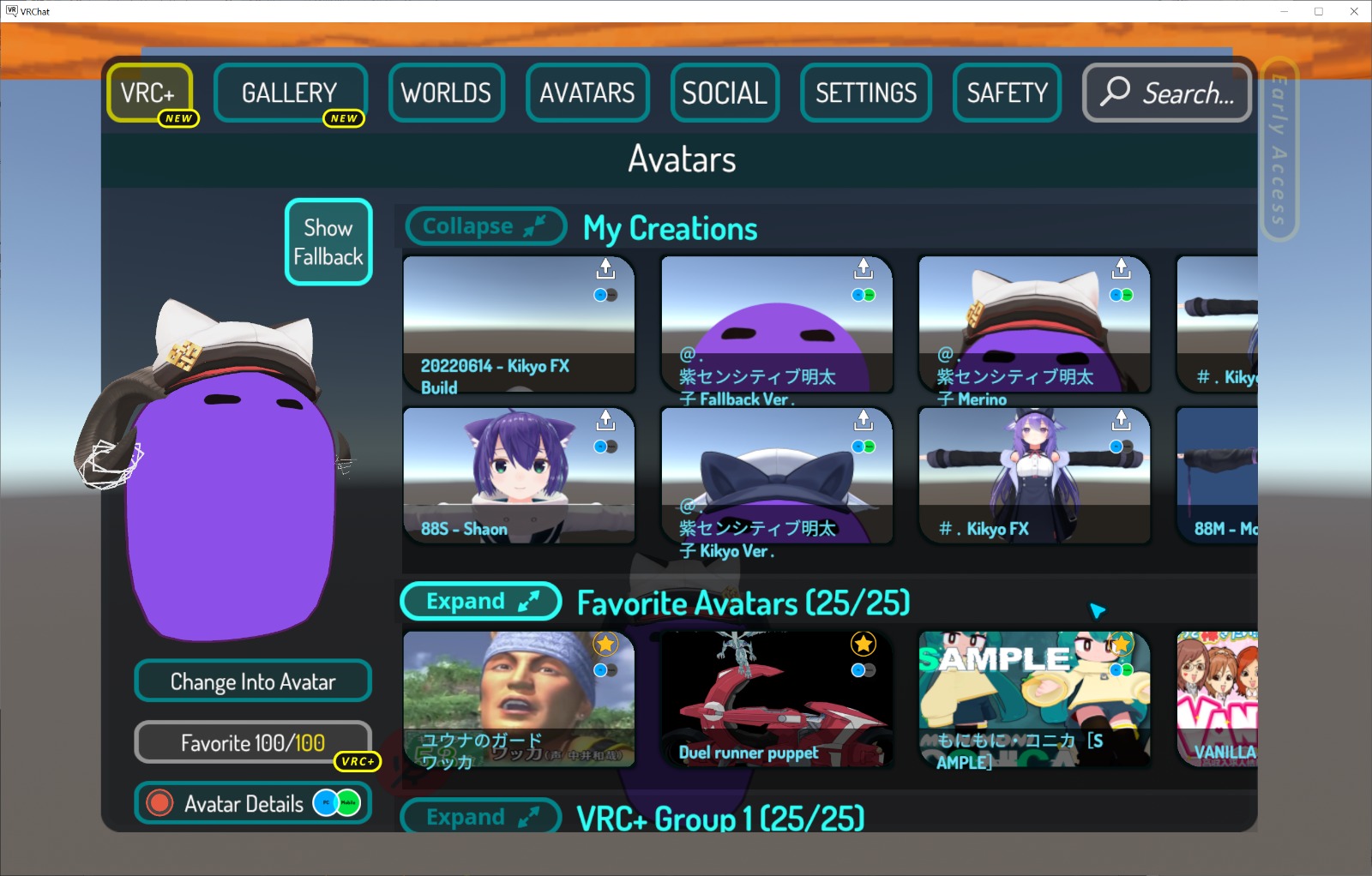

They are administrators of LIHKG VR (連登VR群), a Hong Kong VRChat Telegram group. They organize online activities regularly through instant messaging. Members log in to the virtual world to hang out with each other’s avatars and chat on the audio channels.

But there are no regulations on how users portray themselves in the virtual world. A middle-aged man can appear as a young girl, or a teenager can become a superhero.

The origin of VRChat and virtual social platform

The first avatar-based social platform was launched in 2003 by the San Francisco based online multimedia platform, Second Life. Similar products have since appeared, such as Roblox and Mole Manor in the US and China respectively.

Created by Graham Gaylor and Jesse Joudrey in Texas in the US, VRChat started in 2017 as early access. Similar to Facebook and Instagram, avatar based social networks like VRChat enables users to build social connections online through a video game platform “steam”. In 2020, Siubak rallied for people from LIHKG to join VRChat in a telegram group . Since last year, he has been administrating a chat with 1700 users. Today, LIHKG VRChat has an average of 200 daily users.

The identity crisis

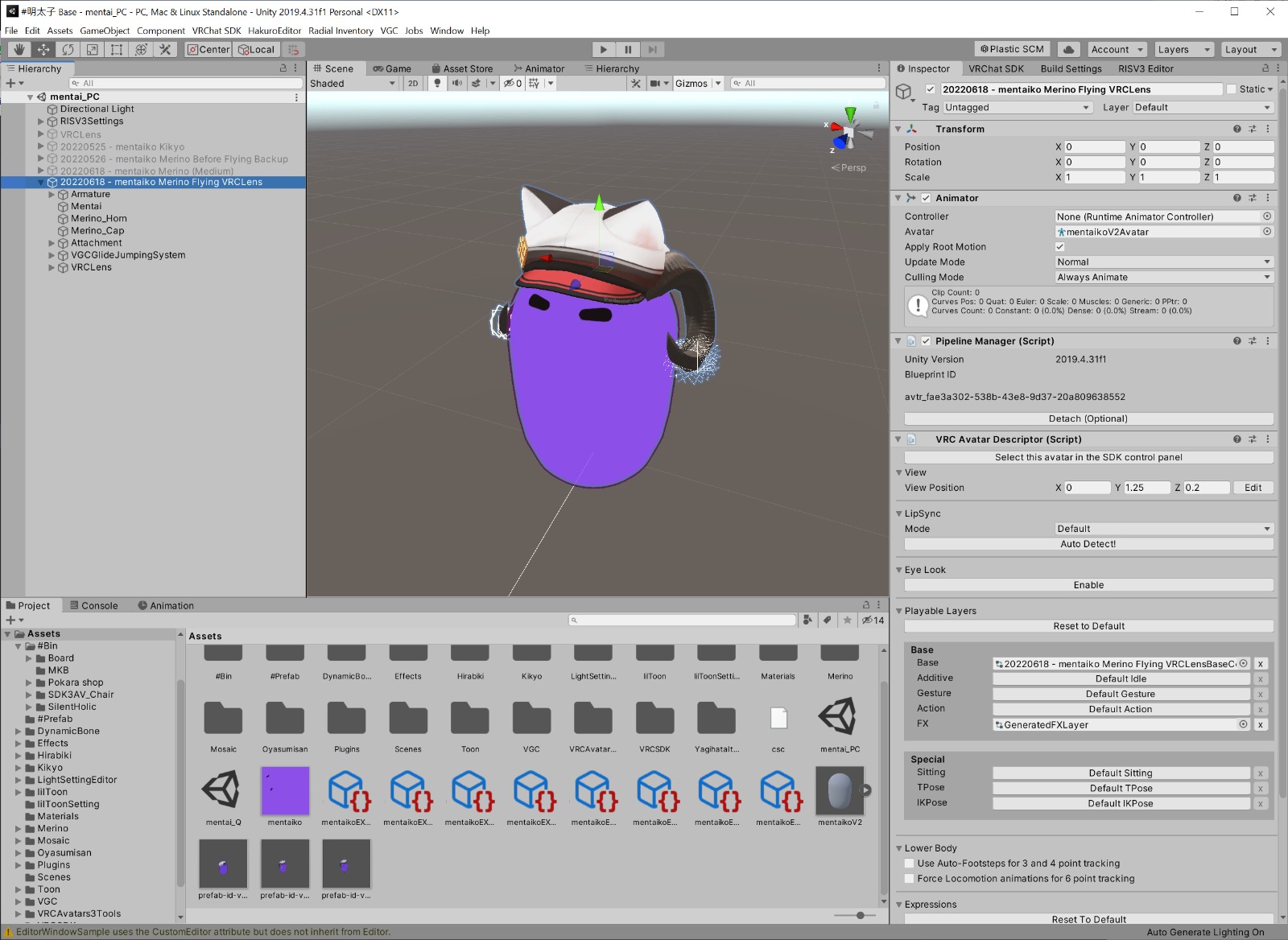

Siubak and Winter manipulate an avatar of a white-haired Japanese anime girl. A male character with purple hair speaks in Cantonese, asking the girl to make cute poses. In the virtual world, users can be anybody they can imagine.

Clinical psychologist Adrian Wong believed some users gain self-esteem in virtual reality when they fail to do so in reality. But when they log off, they may find it difficult to accept their true selves.

“Not everyone can accept being Cinderella, princess before midnight, and a servant after,” Wong said.

He warned that users may then be addicted to the virtual environment, develop psychological problems such as depression and self-harming. due to strong adversity.

Siubak and Winter said they choose their avatars because they are pretty. A study by German researchers in March this year found that players in Japan believe they are their avatars in the real world. Some have used voice changers and adapted female body movements so that they can be recognized as female. Winter said others should respect their identity recognition.

Siubak and Winter said they are not worried that players might use the avatars to hide their true identities. Siubak believed that using a female avatar does not necessarily mean he hates being a man in real-life.

“I think it is a form of self-expression when people choose their avatars," Siubak said. “I treat people I know online as friends in real life,” he added.

“Like on Facebook, people can describe themselves in whatever way they want,” Winter said. “My judgement of a person will not be affected by their virtual avatars,” he added.

The line between reality and virtual

Theresa Wong, administrator of the WhatsApp group “VR-We are Hongkongers”, joined the virtual community because of its surreal socialize functions, and the alternative life experience without real-life boundaries. She claimed her group includes Hong Kong VR-lovers aged 20 to 30+, some of them are married and have kids.

“It breaks geographic and social boundaries. I can follow a foreign friend to visit his hometown through a virtual 3D map, or know friends from the property industry while working in the law sector,” Wong said.

Members in Wong’s group share videos of them playing games together and details about their virtual reality headsets. Wong trusted her friends she has met in virtual reality and shared her feelings and views, even though she knows they may be fake identities.

Winter built his career in real life around VRChat. After being laid off from the information technology sector, he became an administrator of the Japanese virtual reality community, and expanded to teaching photography in virtual schools and got involved in content creation. He spends three to five hours every day in VRChat, for both leisure and business purposes. He believed interpersonal relationships on virtual platforms are not completely fake, and some can even become reality. He once made friends online with a Japanese person, who promoted virtual reality to Japanese automobile manufacturer Nissan Motor.

“We met on virtual reality, but our business relationship is far beyond the platform. We meet every year in Hong Kong,” Winter said.

On the other hand, Siubak treasured reality more after using virtuality. Even when the graphics of the virtual environment improved, Siubak said it is no match to reality.

The importance of physical contact

Siubak, Winter and Theresa Wong admitted there is one irreplaceable feature in real life: physical engagement. But when Siubak excitedly shared hand gestures and facial expression through his avatar, Wong thought that the virtual platform may be a space where you can meet a real-life partner.

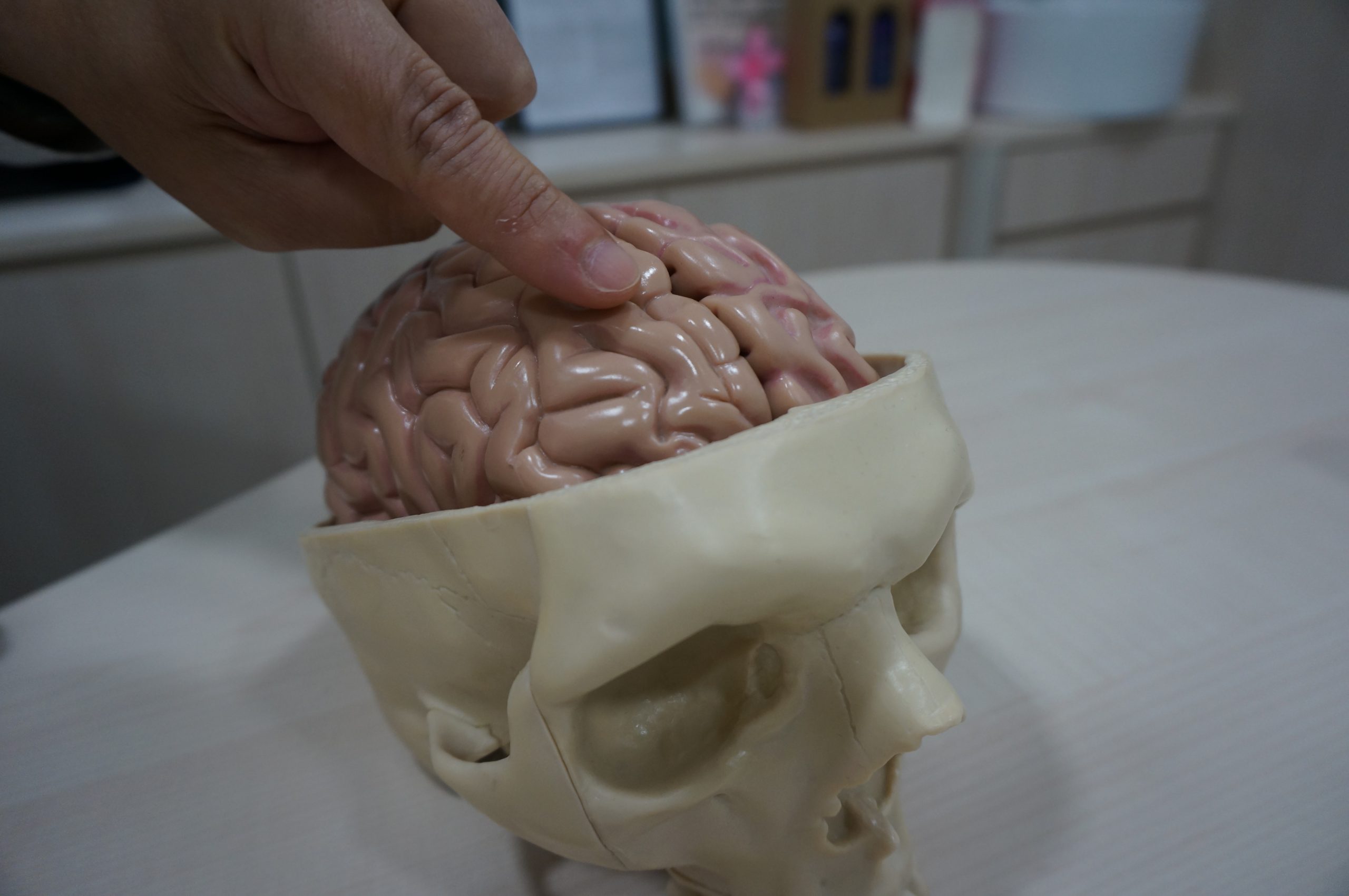

But Adrian Wong explained that non-verbal interaction makes up 70% of human communication, including facial expressions, body gestures and speaking tone.

“Humans need physical contact, like a hug to show intimacy, lending a shoulder to show care without words,” he said.

He doubted if virtual platforms can provide non-verbal interaction in reality. Since children learn about human interaction patterns as they grow up, he is worried that introducing virtual reality to kids may harm their social-cognitive skills.

The problem of cyberbullying in a lawless platform

Theresa Wong believed virtual reality allows her and group members to be their true selves online where they can express opinions freely, especially in the sensitive political environment in Hong Kong. They only welcome fluent Cantonese speakers who type in traditional Chinese characters and share a similar ideology to the rest of the group.

But Adrian Wong is concerned about the higher freedom of speech on virtual social platforms. Although physical damage will not occur, users may fall victim to cyberbullying such as verbal abuse and harassment.

“When these cyberbullying result in real-life casualties, it is hard to review responsibility and punishment when there is no related law,” said Adrian Wong. “It is dangerous if some users who are unable to tell the difference between online and reality, such that they become morally corrupt.”

Siubak, Winter and Theresa Wong claimed that there has been no cyberbullying in their group, and there are regulations for prevention. But Winter admitted that there have been incidents in groups outside Hong Kong, and some users with phantom senses are very sensitive about their avatars being touched.

《The Young Reporter》

The Young Reporter (TYR) started as a newspaper in 1969. Today, it is published across multiple media platforms and updated constantly to bring the latest news and analyses to its readers.

Study finds 70 percent recovered patients suffer from long Covid

Hongkongers’ Book Fair goes online after last-minute cancellation

Comments